Principle of Raman Spectroscopy & Core Components

Principle of Raman Spectroscopy & Core Components

May 28, 2025

Principle of Raman Spectroscopy & Core Components

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful, non-destructive analytical technique used to identify materials and analyse their molecular structure, composition, and crystallinity. It is based on the inelastic scattering of light, a phenomenon known as the Raman Effect, which provides a unique molecular fingerprint for each substance.

What is the Principle of Raman Spectroscopy?

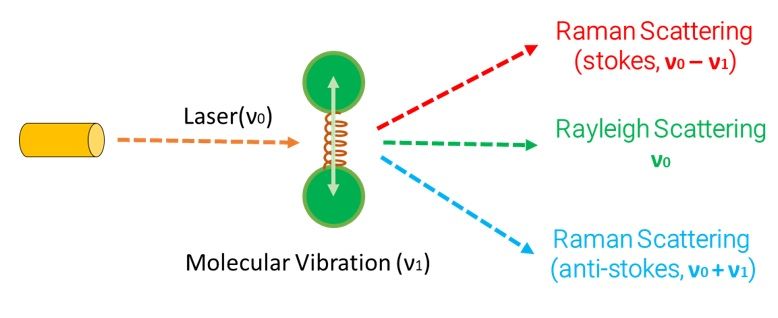

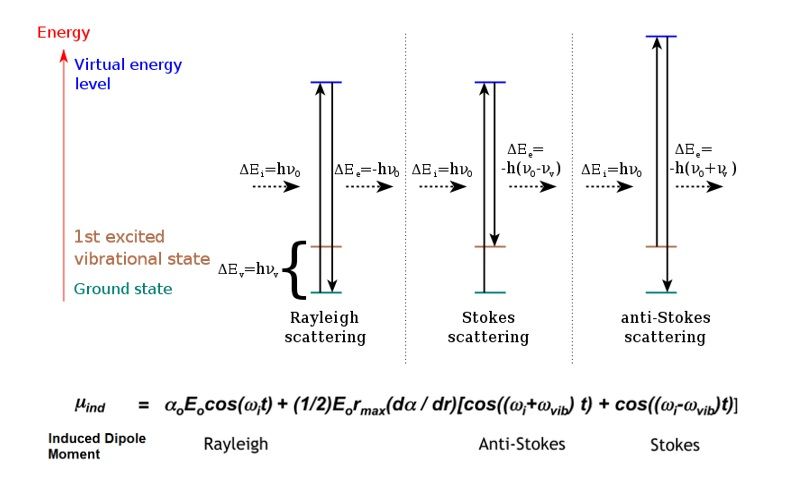

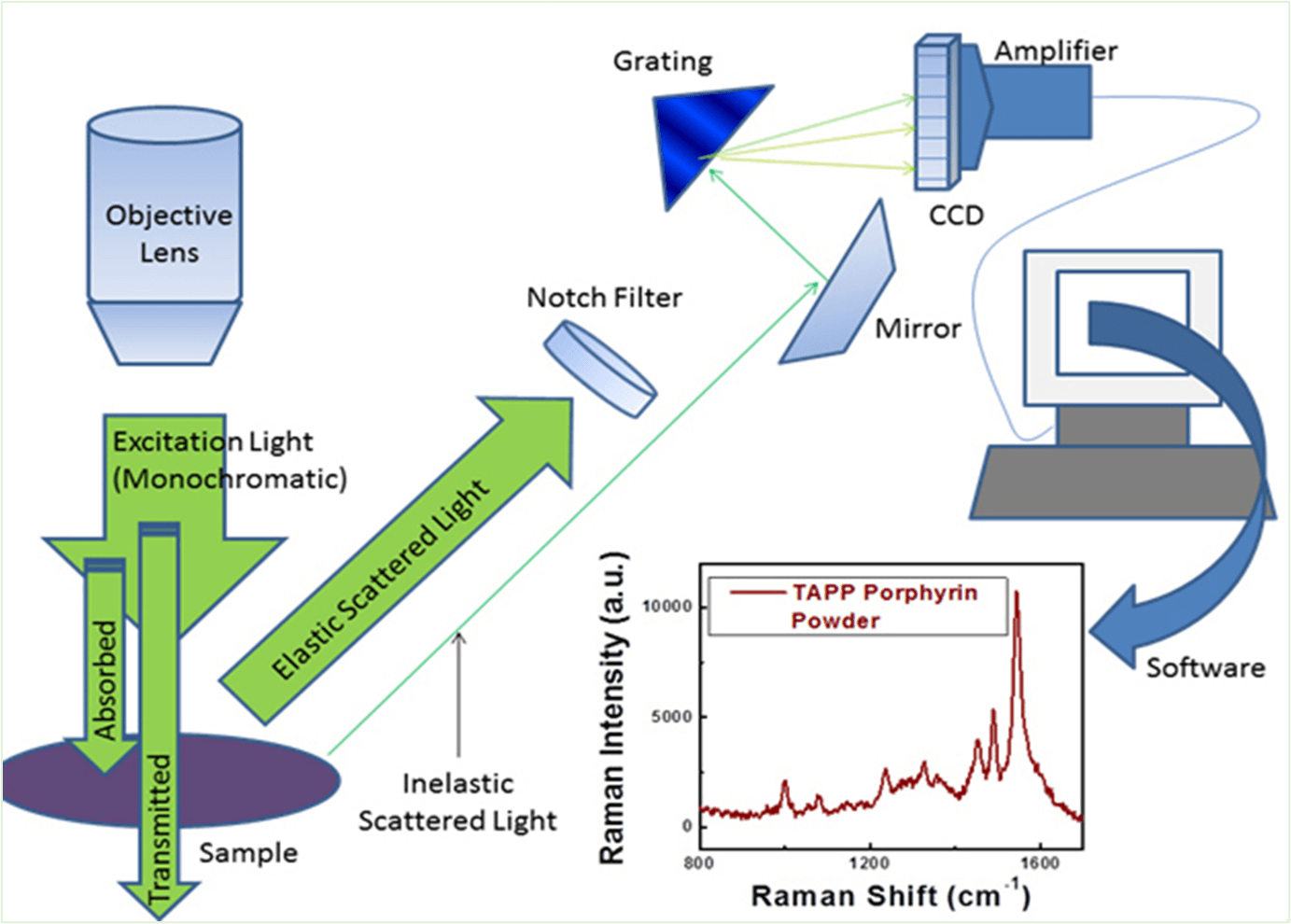

When monochromatic light (typically from a laser) interacts with a material, it is scattered by the molecules in the sample. The majority of this light undergoes elastic scattering, known as Rayleigh scattering, where the scattered photons retain the same energy (or wavelength) as the incident light.

However, a small fraction of photons (~1 in 107) interact with the vibrational energy levels of the molecules and undergo inelastic scattering. This is called Raman scattering, where the photon either loses or gains energy during the interaction. This shift in energy, known as the Raman shift, is directly related to the vibrational modes of the molecule and provides molecular-specific information.

Stokes and Anti-Stokes Scattering Explained

There are two main types of Raman scattering based on the direction of energy exchange:

1. Stokes Raman Scattering:

- Occurs when a photon loses energy to the molecule.

- The molecule is excited from its ground vibrational state to a higher vibrational state.

- The scattered light has a longer wavelength (lower energy) than the incident light.

More intense than Anti-Stokes scattering because most molecules are in the ground state at room temperature.

2. Anti-Stokes Raman Scattering:

- Occurs when the photon gains energy from a molecule already in an excited vibrational state.

- The scattered light has a shorter wavelength (higher energy) than the incident light.

- Less intense than Stokes scattering because fewer molecules are naturally in excited states.

The difference in energy between the incident and scattered photons is called the Raman shift, usually measured in wavenumbers (cm?¹). This shift reflects specific molecular vibrations and forms the basis of Raman spectral analysis.

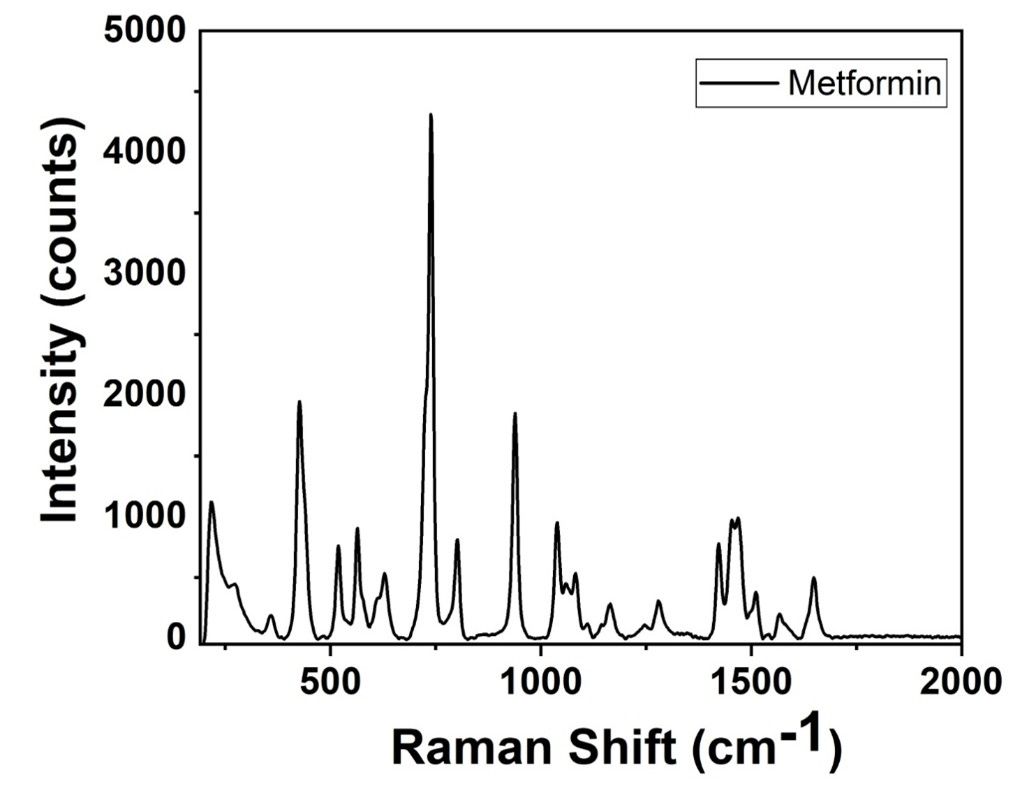

What Is a Raman Spectrum?

A Raman spectrum is a plot of scattered light intensity versus Raman shift. The peaks in the spectrum correspond to vibrational modes within the sample. Because each material has a unique set of molecular vibrations, the spectrum acts like a chemical fingerprint.

The location of each peak reveals information about chemical bonds, functional groups, and molecular structure. The intensity of the peaks provides data on the concentration or environment of those molecules.

Key Features of Raman Spectroscopy

Based on Inelastic Light Scattering: Captures photon-molecule energy exchange to probe vibrational modes.

Molecular Fingerprinting: Identifies materials via unique Raman spectral signatures.

Non-Destructive Testing: Ideal for fragile, valuable, or sensitive samples.

Versatility: Analyses solids, liquids, gases, powders—even through transparent packaging.

Structural Insight: Detects chemical bonds, molecular symmetry, crystallinity, polymorphism, and internal stress or strain in materials.

Core Components of a Raman Spectrometer

The effectiveness of Raman spectroscopy depends heavily on the quality and configuration of its core components. Below is a breakdown of each essential component, its purpose, and common examples used in Raman systems.

Laser Source

Purpose: The laser provides monochromatic light (a single wavelength) to excite the sample molecules. It’s the primary energy source for inducing Raman scattering.

Why it’s needed: Raman scattering is a weak process—only about 1 in 10? to 10? photons undergo inelastic scattering. A strong, stable, and focused laser is crucial for generating measurable Raman signals.

Examples:

- 532 nm (green laser): Offers high Raman intensity, ideal for inorganic and organic materials.

- 785 nm (near-IR laser): Minimizes fluorescence in biological samples.

- 1064 nm (infrared laser): Reduces background fluorescence further, used for sensitive organic or biological specimens.

Sample Illumination and Collection Optics (Microscope or Probe)

Purpose: Directs the laser onto the sample and collects the scattered light (both Raman and Rayleigh).

Why it’s needed: Efficient collection optics ensure maximum scattered photons reach the detector, improving signal quality and resolution.

Examples:

- Objective lenses in microscopes (10x, 50x, 100x) for precise focusing.

- Fibre optic probes for portable or remote sensing Raman systems.

Notch or Edge Filter

Purpose: Blocks the strong Rayleigh-scattered light and allows only Raman-shifted light (Stokes and Anti-Stokes) to pass.

Why it’s needed: Rayleigh scattering is ~10? times more intense than Raman scattering. Without a filter, it would overwhelm the weak Raman signal.

Examples:

- Edge filters: Cut off Rayleigh light below a certain wavelength (common in Stokes Raman setups).

- Notch filters: Block a narrow band around the laser line while transmitting both Stokes and Anti-Stokes signals.

Dispersive Element (Diffraction Grating or Monochromator)

Purpose: Separates the collected Raman-scattered light by wavelength to resolve individual vibrational modes.

Why it’s needed: Raman shifts are small and lie close to the laser wavelength. High-resolution spectral separation is necessary for accurate identification.

Examples:

- Holographic diffraction gratings for high resolution and efficiency.

- Monochromators in older or highly tunable systems.

Detector (Typically CCD Sensor)

Purpose: Captures the dispersed light and converts it into an electrical signal for spectrum generation.

Why it’s needed: Sensitive detection is critical due to the weak intensity of Raman signals. A good detector ensures high signal-to-noise ratio.

Examples:

- CCD (Charge-Coupled Device): Most common for visible/near-IR Raman systems.

- InGaAs detectors: Used for infrared Raman systems (e.g., with 1064 nm lasers).

Data Processing Unit (Computer & Software)

Purpose: Processes raw signals into interpretable spectra and performs peak identification, baseline correction, and database matching.

Why it’s needed: Advanced analysis, calibration, and material identification rely on powerful data handling tools.

Examples:

Spectroscopy software (e.g., TI for Portable, TM for CTR, InsRAM for Handheld Raman Spectrometer produces by TechnoS Instruments) for visualization and interpretation.

IndiRAMID for Database Management and Library search.

Each of these components plays a critical role in ensuring the accuracy, sensitivity, and usability of a Raman spectrometer. Proper selection and integration are essential for tailoring the system to specific applications like material science, pharmaceuticals, forensics, or biomedical research.

Final Thoughts

Raman spectroscopy is a powerful tool with vast applications in science and industry. Understanding its principles and components is the first step toward effectively using or building a Raman spectrometer. In this post, we covered the fundamentals of Raman scattering and broke down the essential hardware that makes Raman spectroscopy possible—from lasers and filters to spectrometers and detectors. In Part 2 of this blog series, we’ll guide you through the selection process for each component based on your application, budget, and performance requirements.

Related Articles

- Gemstone Identification with Raman Spectroscopy: Preserving Purity, Authenticity, and Trust in the Industry

- Field Testing Simplified: Benefits of Portable Raman Spectrometers

- Raman Spectroscopy: A Transformative Tool Across Science, Industry, and Society

- Behind the Pills Identifier: Unmasking Illicit Drugs with Raman Spectroscopy

- Crystal Clarity: Understanding Quartz Through Raman Spectroscopy

- IndiRAM Raman Spectrometer for identification of Excipients in Pharmaceutical Drugs

- Innovations in Raman Spectroscopy: TechnoS at the Forefront

- Microplastic Contamination Detection in Food Grains: A Raman Spectroscopy Approach

- Powering the Future: How Raman Spectroscopy is Advancing Battery Material Analysis